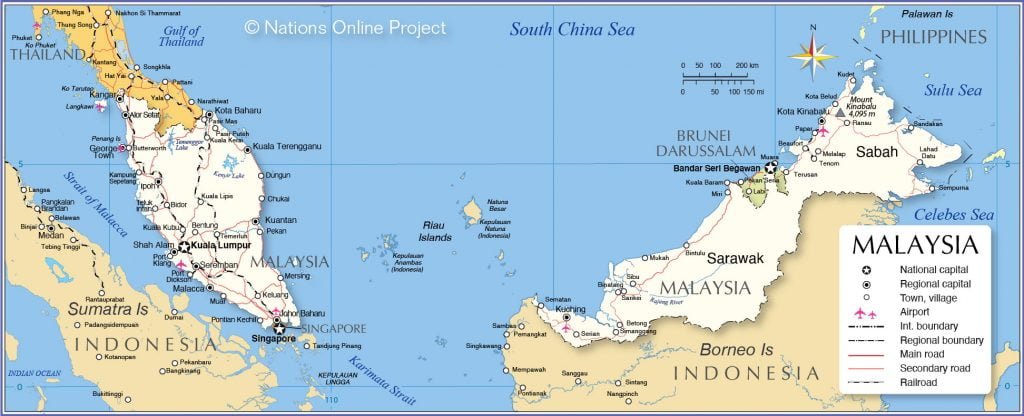

Malaysia, officially known as the Federation of Malaysia, is a captivating country located in Southeast Asia. Its unique geographical features divide it into two distinct regions, namely Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo’s East Malaysia, with the South China Sea acting as a natural boundary Update 02/24/2026

Peninsular Malaysia shares both land and maritime borders with Thailand, and maritime borders with Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

On the other hand, East Malaysia shares land and maritime borders with Brunei and Indonesia, along with a maritime border with the Philippines and Vietnam.

Serving as the national capital and the largest city, Kuala Lumpur houses the legislative branch of the federal government, while the administrative center, Putrajaya, serves as the seat for the executive and judicial branches.

With a population exceeding 32 million people, Malaysia stands as the 45th-most populous country globally. A notable landmark is found in Tanjung Piai, marking the southernmost point of continental Eurasia.

Due to its tropical location, Malaysia is recognized as one of the 17 megadiverse countries, boasting a remarkable array of unique and indigenous species.

The roots of Malaysia can be traced back to the Malay kingdoms, which gradually fell under British control during the 18th century, including the British Straits Settlements protectorate. During World War II, British Malaya, alongside neighboring British and American colonies, was occupied by the Empire of Japan.

After three years of Japanese occupation, peninsular Malaysia was unified as the Malayan Union in 1946, eventually transforming into the Federation of Malaya in 1948.

On the historic date of August 31, 1957, Malaysia gained independence. Subsequently, the independent Malaya merged with the British crown colonies of North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore on September 16, 1963, to form the present-day Malaysia. However, in August 1965, Singapore separated from the federation to become an independent country.

The cultural fabric of Malaysia is woven with rich diversity, reflected in its multiethnic and multicultural society, which significantly influences its political landscape.

Malays comprise approximately half of the population, while Chinese, Indians, and indigenous peoples constitute significant minority groups.

The official language of the country is Malaysian Malay, which serves as the standardized form of the Malay language. English also retains its prominence as a widely used second language.

While Islam holds the status of the country’s established religion, the constitution guarantees religious freedom to non-Muslims. Malaysia follows the Westminster parliamentary system, with the monarch being an elected figure chosen from among the nine state sultans every five years. The head of government is the Prime Minister.

Since achieving independence, Malaysia has experienced impressive economic growth, with an average annual GDP growth rate of 6.5% for nearly five decades.

While the economy has traditionally relied on its abundant natural resources, it is now expanding into sectors such as science, tourism, commerce, and medical tourism.

As a newly industrialized market economy, Malaysia ranks as the third-largest economy in Southeast Asia and the 36th-largest globally. The country plays an active role in various international organizations, including being a founding member of ASEAN, EAS, and OIC, as well as a member of APEC, the Commonwealth, and the Non-Aligned Movement.

Etymology Update 02/24/2026

The country we now know as Malaysia has a fascinating etymology that sheds light on its rich history and cultural heritage. The name “Malaysia” is a combination of the word “Malays” and the Latin-Greek suffix “-ia/-ία,” which can be translated as “land of the Malays.”

The origin of the term “Melayu” has given rise to various theories. One theory suggests that it may have derived from the Sanskrit word “Himalaya,” referring to high mountainous regions.

Another theory proposes the Tamil words “malai” and “ur,” meaning “mountain” and “city/land,” respectively. Yet another suggestion is that it originated from the Pamalayu campaign, while some believe it comes from a Javanese word meaning “to run,” which gave rise to the name of the Sungai Melayu (Melayu River) due to its strong current.

Similar-sounding variants of the name have been found in older accounts, referring to areas in Sumatra or the larger region around the Strait of Malacca.

The Sanskrit text Vayu Purana, dating back to the first millennium CE, mentioned a land called “Malayadvipa,” which some scholars identify as the modern Malay Peninsula.

Other historical accounts, such as Ptolemy’s Geographia and Yijing’s writings, have also referred to “Malayu” and its association with different parts of Sumatra, particularly Palembang, where the founder of the Malacca Sultanate is believed to have originated from.

Over time, the Melayu Kingdom became linked with the Sungai Melayu. It later became associated with Srivijaya and remained connected to various regions in Sumatra, particularly Palembang.

It is thought that the term “Melayu” developed into an ethnonym during the rise of the Malacca Sultanate in the 15th century. The process of Islamization played a significant role in establishing an ethnoreligious identity in Malacca, and “Melayu” began to be used interchangeably with “Melakans.”

It likely referred specifically to local Malay speakers who were loyal to the Malaccan Sultan. The initial Portuguese use of the term “Malayos” reflected this association with the ruling people of Malacca.

As trade flourished in Malacca, “Melayu” became associated with Muslim traders and gradually extended its cultural and linguistic connotations. The importance of Malacca and later Johor in Malay culture, supported by the British, led to the term “Malay” becoming primarily linked to the Malay Peninsula rather than Sumatra.

Before European colonization, the native inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula referred to their land as Tanah Melayu, meaning “Malay Land.” In the racial classification proposed by German scholar Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, the native populations of maritime Southeast Asia were grouped together as the Malay race.

In 1831, following French navigator Jules Dumont d’Urville’s expedition to Oceania, he proposed the terms Malaysia, Micronesia, and Melanesia to differentiate these Pacific cultures and island groups from Polynesia.

Dumont d’Urville described Malaysia as “an area commonly known as the East Indies.” In 1850, English ethnologist George Samuel Windsor Earl suggested naming the islands of Southeast Asia as “Melayunesia” or “Indunesia,” with a preference for the former.

The name Malaysia began to be used to label the Malay Archipelago. In modern usage, “Malay” refers to an ethnoreligious group of Austronesian people predominantly inhabiting the Malay Peninsula, parts of Sumatra, the coast of Borneo, and smaller surrounding islands.

When the state gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1957, it was named the Federation of Malaya. This name was chosen over other potential options, such as Langkasuka, after a historic kingdom situated in the upper section of the Malay Peninsula during the first millennium CE.

The name Malaysia was adopted in 1963 when the existing states of the Federation of Malaya, along with Singapore, North Borneo, and Sarawak, formed a new federation.

One theory suggests that the name was selected to reflect the inclusion of Singapore, North Borneo, and Sarawak into Malaya in 1963. Interestingly, politicians in the Philippines also considered renaming their state Malaysia before the present-day country took on the name.

History

It covers significant events such as the arrival of traders and settlers from India and China, the rise of kingdoms like Langkasuka and Srivijaya, the founding of the Malacca Sultanate, and the subsequent colonization by European powers such as Portugal, the Netherlands, and Britain.

It also mentions the Japanese occupation during World War II, the post-war period of nationalism and independence movements, the Malayan Emergency, the formation of the Federation of Malaya, and the eventual establishment of Malaysia as a federation including Sabah and Sarawak.

The history continues with the challenges faced during the early years of federation, including conflicts with Indonesia, communist insurgencies, racial tensions, and the implementation of economic policies like the New Economic Policy.

It also highlights Malaysia’s economic growth, the Asian financial crisis, and more recent political developments, including the 1MDB scandal and the COVID-19 pandemic. The information provided gives a comprehensive overview of Malaysia’s historical journey up until the recent political developments.

Government and politics

Malaysia is indeed a federal constitutional elective monarchy, with a parliamentary system of government influenced by the British Westminster system.

The head of state is the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, who is elected from among the hereditary rulers of the Malay states for a five-year term. The King’s role is largely ceremonial, and the position is rotated among the nine hereditary rulers. The executive power is vested in the Cabinet, led by the Prime Minister, who is the head of government.

The federal parliament consists of the House of Representatives and the Senate, and legislative power is divided between the federal and state legislatures.

Members of the House of Representatives are elected for a maximum term of five years, while senators serve three-year terms. The parliament follows a multi-party system, and the government is elected through a first-past-the-post system. The executive, legislative, and judicial branches operate within the framework of Malaysia’s legal system, which is based on English Common Law.

Ethnicity and race play a significant role in Malaysian politics, and affirmative actions have been implemented to uplift the bumiputera, which includes Malays and indigenous tribes, through policies such as the New Economic Policy.

These policies provide preferential treatment in various aspects of life, which has caused some interethnic resentment. There are ongoing debates regarding the role of Islamism and secularism in Malaysian society, and the influence of Islam in the legal system.

Malaysia’s democracy and press freedom rankings have seen fluctuations in recent years. It is classified as a flawed democracy in the Democracy Index, and its ranking in the Press Freedom Index has shown improvement but also faced setbacks.

Malaysia’s ranking in the Corruption Perceptions Index indicates above-average levels of corruption, and high-profile cases such as the 1MDB scandal have drawn attention to corruption issues in the country.

It’s important to note that political situations and rankings may evolve over time, so it’s advisable to refer to up-to-date sources for the most current information on Malaysia’s political system and social dynamics.

Administrative divisions

Malaysia is a federation consisting of 13 states and three federal territories. These are divided into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia, which comprises 11 states and two federal territories, and East Malaysia, which consists of two states and one federal territory.

The governance of the states is shared between the federal government and the state governments, with each having specific powers and responsibilities.

The federal government directly administers the federal territories. Each state has a unicameral State Legislative Assembly, and its members are elected from single-member constituencies.

The state governments are headed by Chief Ministers, who are typically members of the majority party in the State Legislative Assembly. In states with hereditary rulers, the Chief Minister is usually required to be a Malay and appointed by the ruler based on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. State elections, except for those in Sarawak, are generally held concurrently with federal elections.

Lower-level administration is carried out by local authorities, including city councils, district councils, and municipal councils. The federal and state governments can also establish autonomous statutory bodies to handle specific tasks.

Local authorities in areas outside the federal territories are under the jurisdiction of the respective state governments, as mandated by the federal constitution. However, the federal government has sometimes intervened in the affairs of state local governments. There are a total of 154 local authorities in Malaysia, including city councils, municipal councils, and district councils.

The 13 states in Malaysia have historical ties to Malay kingdoms, and nine of the 11 states in Peninsular Malaysia, known as the Malay states, retain their royal families.

The King, elected by and from the nine rulers, serves a five-year term. Governors are appointed by the King for the states without monarchies, following consultations with the Chief Minister of the respective state. Each state has its own written constitution.

Sabah and Sarawak enjoy more autonomy compared to other states, including separate immigration policies, controls, and a unique residency status. However, federal intervention, developmental disparities, and disputes over oil royalties have occasionally led to discussions about secession by leaders in states such as Penang, Johor, Kelantan, Sabah, and Sarawak. These discussions have not progressed into serious independence movements.

Please note that the political situation and administrative divisions may have evolved since my last update in September 2021. For the most up-to-date information, it is advisable to refer to current sources on Malaysia’s governance and administrative structure.

Foreign relations and military

Malaysia is a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and participates in various international organizations including the United Nations, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Developing 8 Countries, and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

The country has chaired ASEAN, the OIC, and the NAM in the past. Additionally, Malaysia is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. Kuala Lumpur hosted the first East Asia Summit in 2005.

Malaysia’s foreign policy is based on the principle of neutrality and maintaining peaceful relations with all countries, regardless of their political system.

The government places a high priority on the security and stability of Southeast Asia and seeks to strengthen relations with other countries in the region.

Malaysia aims to portray itself as a progressive Islamic nation while also fostering ties with other Islamic states. The country upholds national sovereignty and the right of each country to control its domestic affairs. Malaysia has signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

The Spratly Islands, a disputed territory in the South China Sea, has been a contentious issue for many states in the region. Malaysia historically avoided conflicts with China but has become more active in condemning China’s encroachment into Malaysian territorial waters and breach of airspace.

Malaysia resolved land claims with Brunei in 2009 and committed to resolving maritime border issues. The Philippines has a dormant claim to the eastern part of Sabah, and tensions have arisen due to Singapore’s land reclamation. Minor maritime and land border disputes also exist with Indonesia.

The Malaysian Armed Forces consist of the Malaysian Army, Royal Malaysian Navy, and Royal Malaysian Air Force. Military service is voluntary, and the required age is 18.

The military budget accounts for 1.5% of the country’s GDP, employing 1.23% of Malaysia’s manpower. Malaysia has contributed to various UN peacekeeping missions, demonstrating its commitment to international peace and security.

The Five Power Defence Arrangements, a regional security initiative, involves joint military exercises among Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

Malaysia has also conducted joint exercises and war games with countries such as Brunei, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and the United States. Joint security force exercises have been held among Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam to address issues like illegal immigration, piracy, and smuggling. Malaysia has increased border security to address concerns about the potential spillover of extremist militant activities from neighboring regions.

Please note that the political landscape, international relations, and defense policies may have evolved since my last update in September 2021. For the most up-to-date information, it is advisable to refer to current sources on Malaysia’s international relations and defense initiatives.

Human rights

In Malaysia, homosexuality is indeed illegal, and authorities have imposed punishments including caning and imprisonment for individuals engaging in same-sex activities.

Human trafficking and sex trafficking are significant issues in Malaysia as well. There have been reports of vigilante executions and beatings targeting LGBT individuals in the country.

The legality of homosexuality has also been a prominent aspect of Anwar Ibrahim’s sodomy trials, with Anwar and various international organizations characterizing them as politically motivated.

The United Nations’ Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, along with Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have expressed concerns regarding the trials.

The death penalty is currently used for serious crimes such as murder, terrorism, drug trafficking, and kidnapping in Malaysia. However, in June 2022, the Malaysian Law Minister Wan Junaidi pledged to abolish capital punishment and replace it with alternative forms of punishment at the discretion of the court.

Please note that the situation regarding laws, policies, and human rights issues in Malaysia may have evolved since my last update in September 2021. It is recommended to refer to current and reliable sources for the most up-to-date information.

Geography

Malaysia is the 66th largest country in the world, with a land area of 329,613 square kilometers (127,264 square miles). It shares land borders with Thailand in West Malaysia, and Indonesia and Brunei in East Malaysia.

There is a narrow causeway and bridge connecting Malaysia to Singapore. Malaysia also has maritime boundaries with Vietnam and the Philippines. The land borders are defined by geographical features such as rivers and canals, while some maritime boundaries are subject to ongoing disputes.

Brunei is almost an enclave within Malaysia, with the state of Sarawak dividing it into two parts. Malaysia is unique in that it has territory on both the Asian mainland and the Malay archipelago.

The Strait of Malacca, located between Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia, is a crucial trade route, handling 40% of global trade.

Both Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia have similar landscapes, characterized by coastal plains, hills, and mountains. Peninsular Malaysia constitutes 40% of the country’s land area and stretches 740 kilometers (460 miles) from north to south. The Titiwangsa Mountains divide the peninsula into east and west coasts.

The mountain ranges in the peninsula are heavily forested, mainly composed of granite and other igneous rocks. The coastal plains reach a maximum width of 50 kilometers (31 miles), with a coastline that is nearly 1,931 kilometers (1,200 miles) long.

East Malaysia, located on the island of Borneo, has a coastline of 2,607 kilometers (1,620 miles). It consists of coastal regions, hills, valleys, and a mountainous interior.

The Crocker Range extends northwards from Sarawak, dividing the state of Sabah. Mount Kinabalu, standing at 4,095 meters (13,435 feet), is the highest mountain in Malaysia and is situated in the Kinabalu National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Sarawak is home to the Mulu Caves, the largest cave system in the world, located in Gunung Mulu National Park, also a World Heritage Site. The Rajang River is the longest river in Malaysia.

Surrounding the two halves of Malaysia are numerous islands, with Banggi being the largest. The climate in Malaysia is equatorial, characterized by annual monsoons.

The temperature is moderated by the surrounding oceans, and humidity is generally high. The average annual rainfall is 250 centimeters (98 inches).

The climate varies between the Peninsula and the East, with the peninsula experiencing direct influence from the mainland, while the East has more maritime weather. Local climates can be categorized into highland, lowland, and coastal regions.

Climate change is expected to bring about sea level rise, increased rainfall, and associated risks of floods and droughts.

Biodiversity and conservation

Malaysia signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity in 1993 and became a party to the convention in 1994. The country has developed a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan to address biodiversity conservation.

Malaysia is considered megadiverse, with a significant number of species and high levels of endemism. It is estimated to be home to 20% of the world’s animal species.

The forests in the mountains of Borneo, which are diverse and isolated from lowland forests, contribute to high levels of endemism.

Malaysia boasts around 210 mammal species, over 620 bird species (many of which are endemic to the mountains of Peninsular Malaysia), 250 reptile species (including approximately 150 snake species and 80 lizard species), about 150 frog species, and thousands of insect species.

The country’s exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea is 1.5 times larger than its land area, covering 334,671 square kilometers (129,217 square miles) and includes the Coral Triangle, a biodiversity hotspot. The waters around Sipadan island are recognized as the most biodiverse in the world, and the Sulu Sea, which borders East Malaysia, is another biodiversity hotspot.

Malaysia is known for its caves, which are rich in unique biodiversity and attract ecotourism enthusiasts from around the world. Nearly 4,000 fungal species, including lichen-forming species, have been recorded in Malaysia, but there are likely many more yet to be discovered.

In terms of forest cover, approximately two-thirds of Malaysia was forested in 2007, with some forests believed to be 130 million years old. Dipterocarps dominate the forests, with lowland forests prevalent below 760 meters (2,490 feet).

However, extensive logging and land cultivation practices have caused significant deforestation and environmental degradation.

Over 80% of Sarawak’s rainforest has been logged, and more than 60% of the Peninsula’s forest has been cleared. Deforestation, primarily driven by the palm oil industry, poses a severe threat to the country’s forests, with predictions that they could be entirely extinct by 2020. Habitat destruction has led to the extinction of certain species, and remaining forests are mainly found in reserves and national parks.

Environmental degradation also affects marine ecosystems, with habitat destruction, illegal fishing practices (such as dynamite fishing and poisoning), and uncontrolled tourism posing threats to marine life.

The population of leatherback turtles, for example, has declined by 98% since the 1950s. Hunting and overconsumption of animals, along with wildlife trafficking, further endanger various species.

The Malaysian government aims to strike a balance between economic growth and environmental protection, although it has faced criticism for favoring business interests over the environment.

Efforts have been made to mitigate the impact of deforestation and pollution, with some state governments taking measures to address the issue. The federal government aims to reduce logging by 10% annually.

National parks have been established to conserve biodiversity, with 28 parks in total, 23 in East Malaysia and five in the Peninsula. Conservation measures, such as limiting tourism in biodiverse areas like Sipadan island, have been implemented. The government has also engaged in discussions with Brunei and Indonesia to establish consistent anti-trafficking laws to combat wildlife trafficking.

Economy Update 02/24/2026

Malaysia has a relatively open state-oriented and newly industrialized market economy. It ranks as the world’s 36th-largest economy by nominal GDP and the 31st-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP).

The service sector contributes the largest share to the country’s GDP, accounting for 53.6%, followed by the industrial sector at 37.6%, and the agricultural sector at approximately 8.8%. The official unemployment rate in Malaysia is low, standing at 3.9%. The country’s foreign exchange reserves are the 24th-largest globally, and it has a labor force of around 15 million, ranking as the 34th-largest in the world.

Malaysia’s automotive industry is significant, ranking as the 22nd-largest in terms of production. It is also the 23rd-largest exporter and 25th-largest importer globally.

However, economic disparities exist among different ethnic groups in the country. While the Chinese population constitutes about one-quarter of the total population, they account for 70% of the country’s market capitalization.

Chinese businesses in Malaysia are part of the larger bamboo network, which is a network of overseas Chinese businesses in Southeast Asia with common family and cultural ties.

International trade, facilitated by the strategic shipping route through the Strait of Malacca, and manufacturing are key sectors driving Malaysia’s economy.

The country exports natural and agricultural resources, with petroleum being a major export. Malaysia has been a leading producer of tin, rubber, and palm oil in the world. Although manufacturing has been a dominant sector, Malaysia’s economic structure has been diversifying. It remains one of the world’s largest producers of palm oil.

Tourism plays a significant role in Malaysia’s economy as the third-largest contributor to GDP after manufacturing and commodities sectors. In 2019, tourism contributed approximately 15.9% to the total GDP.

Malaysia ranked as the 14th most visited country globally and the fourth most visited in Asia in 2019, with over 26.1 million visits. The country’s international tourism receipts amounted to $19.8 billion in the same year.

Malaysia has also emerged as a center of Islamic banking and has a high number of female workers in that industry. Knowledge-based services are expanding, and the country exported high-tech products worth $92.1 billion in 2020, the second-highest in the ASEAN region after Singapore.

Malaysia has been recognized for its innovation, ranking 36th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021 and 32nd in the Global Competitiveness Report in 2022.

Infrastructure Update 02/24/2026

Railway transport in Malaysia is operated by the state and covers a distance of approximately 2,783 kilometers (1,729 miles). The country has the world’s 26th-largest road network, with approximately 238,823 kilometers (148,398 miles) of roads as of 2016. Malaysia also boasts the world’s 22nd-longest inland waterway system, spanning 7,200 kilometers (4,474 miles).

Malaysia has 114 airports, with Kuala Lumpur International Airport being the busiest. Located in the Sepang District, south of Kuala Lumpur, it is the twelfth-busiest airport in Asia. Among the seven federal ports, Port Klang is the major port and the thirteenth-busiest container port.

In terms of telecommunications, Malaysia’s network is second only to Singapore’s in Southeast Asia. The country has 4.7 million fixed-line subscribers and over 30 million cellular subscribers.

Malaysia has established various industrial parks, including Technology Park Malaysia and Kulim Hi-Tech Park, with a total of 200 industrial parks. The majority of the population, over 95%, has access to fresh water, primarily sourced from groundwater.

The energy infrastructure sector in Malaysia is dominated by Tenaga Nasional, the largest electric utility company in Southeast Asia. The National Grid provides electricity connections to customers. Sarawak Energy and Sabah Electricity are the other two electric utility companies in the country. Malaysia has a total power generation capacity of over 29,728 megawatts, with energy production primarily based on oil and natural gas. The country’s oil and natural gas reserves are the fourth largest in the Asia-Pacific region.

While there has been significant development in rural areas, they still lag behind the more developed West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Rural populations have less access to the telecommunication network compared to urban areas.

Demographics Update 02/24/2026

According to the Malaysian Department of Statistics, the population of Malaysia was 32,447,385 in 2020, making it the 42nd most populous country in the world. The population is estimated to be growing at a rate of 1.54 percent per year as of 2012. Malaysia has an average population density of 96 people per square kilometer, ranking it 116th in the world for population density.

The population is divided along ethnic lines, with 69.7 percent considered bumiputera, which includes Malays and indigenous groups in Sabah and Sarawak. Malays, who are defined in the constitution as Muslims who practice Malay customs and culture, play a dominant role politically. Non-Malay indigenous groups in Sabah and Sarawak, such as the Dayaks, Kadazan-Dusun, Melanau, and Bajau, also have bumiputera status. In addition, there are indigenous groups known as Orang Asli on the peninsula. Malaysian Chinese make up 22.5 percent of the population, while Malaysian Indians constitute 6.8 percent.

Citizenship in Malaysia is not automatically granted to those born in the country, but it is granted to a child born to two Malaysian parents outside Malaysia. Dual citizenship is not permitted. Citizenship in Sabah and Sarawak is distinct from citizenship in Peninsular Malaysia for immigration purposes. Malaysian citizens are issued a biometric smart chip identity card called MyKad at the age of 12, which they must carry at all times.

The population is concentrated on Peninsular Malaysia, where approximately 20 million out of 28 million Malaysians reside. Around 70 percent of the population is urban. The country has a significant number of migrant workers, estimated to be over 3 million, accounting for about 10 percent of the population. There is also a sizable population of refugees and asylum seekers in Malaysia, with approximately 171,500 individuals. The majority of refugees come from Burma and the Philippines.

Religion Update 02/24/2026

According to the Malaysian constitution, freedom of religion is granted, while Islam is established as the “religion of the Federation.”

The Population and Housing Census 2020 data shows a strong correlation between ethnicity and religious beliefs in Malaysia. Approximately 63.5% of the population practices Islam, 18.7% practice Buddhism, 9.1% Christianity, 6.1% Hinduism, and 1.3% practice Confucianism, Taoism, and other traditional Chinese religions. About 2.7% either declared no religion, practiced other religions, or did not provide any information.

The states of Sarawak, Penang, and the federal territory of Kuala Lumpur have non-Muslim majorities. Sunni Islam of the Shafi’i school of jurisprudence is the dominant branch of Islam in Malaysia, while 18% identify as non-denominational Muslims. The Malaysian constitution defines Malays as those who are Muslim, speak Malay regularly, practice Malay customs, and have lived in or have ancestors from Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Statistics from the 2010 Census show that 83.6% of the Chinese population identifies as Buddhist, with significant numbers also following Taoism (3.4%) and Christianity (11.1%).

The majority of the Indian population practices Hinduism (86.2%), with a significant minority identifying as Christians (6.0%) or Muslims (4.1%). Among the non-Malay bumiputera community, Christianity is the predominant religion (46.5%), with an additional 40.4% identifying as Muslims.

Muslims in Malaysia are obliged to follow the decisions of the Syariah Courts (Shariah courts) in matters concerning their religion.

These courts operate under the Shafi’i legal school of Islam, which is the main madh’hab in Malaysia. The jurisdiction of Syariah courts is limited to Muslims and covers matters such as marriage, inheritance, divorce, apostasy, religious conversion, and custody, among others. Criminal and civil offenses fall under the jurisdiction of the Civil Courts, and they do not hear cases related to Islamic practices.

Languages

The official and national language of Malaysia is Malaysian Malay, which is a standardized form of the Malay language. The previous terminology used by the government was Bahasa Malaysia (Malaysian language), but now the government policy uses “Bahasa Melayu” (Malay language) to refer to the official language, and both terms are still in use. The National Language Act 1967 designates the Latin script (Rumi) as the official script of the national language, but it does not prohibit the use of the traditional Jawi script.

English is widely used as a second language in Malaysia, and its use is allowed for certain official purposes under the National Language Act of 1967. In Sarawak, English is an official state language alongside Malaysian. Historically, English was the de facto administrative language, but after the 1969 race riots, Malay became predominant. Malaysian English, also known as Malaysian Standard English, is a form of English influenced by British English. Manglish, a colloquial form of English with Malay, Chinese, and Tamil influences, is also commonly used in business settings. While the government discourages the use of non-standard Malay, it has limited power to penalize those who use what is perceived as improper Malay in their advertisements.

In addition to Malay and English, Malaysia is home to speakers of many other languages. There are speakers of 137 living languages in the country, with 41 of them found in Peninsular Malaysia. The indigenous tribes of East Malaysia have their own languages, such as Iban in Sarawak and Dusunic and Kadazan languages in Sabah. Chinese Malaysians predominantly speak various Chinese dialects, including Mandarin, Cantonese, and Hokkien. Tamil is primarily spoken by the majority of Malaysian Indians. There are also a small number of Malaysians of European ancestry who speak creole languages such as Portuguese-based Malaccan Creoles and Spanish-based Chavacano language.

Health Update 02/24/2026

Malaysia has a well-developed healthcare system that consists of both a universal healthcare system provided by the Ministry of Health (MOH) and a co-existing private healthcare system. The public healthcare system offers highly subsidized services through a network of public hospitals and clinics. This two-tier system ensures that healthcare is accessible to the population.

The healthcare expenditure in Malaysia amounted to 3.83% of its GDP in 2019, reflecting the country’s investment in the healthcare sector. The life expectancy in Malaysia is relatively high, with an overall average of 76 years at birth in 2020 (74 years for males and 78 years for females). The infant mortality rate is 7 deaths per 1000 births, indicating a relatively low rate of infant deaths.

Malaysia’s total fertility rate in 2020 was 2.0, which is slightly below the replacement level of 2.1. The crude birth rate was 16 per 1000 people, while the crude death rate was 5 per 1000 people in the same year. These demographic indicators provide insights into the country’s population dynamics.

In terms of health issues, coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death among Malaysian adults, accounting for 17% of medically certified deaths in 2020. Pneumonia is another significant cause of death, representing 11% of the total deaths. Transport accidents pose a major health hazard in Malaysia, as the country has one of the highest traffic fatality rates relative to its population. Smoking is also a prominent health issue that affects the population.

The development and efficiency of Malaysia’s healthcare system have contributed to the growth of medical tourism in the country. The availability of quality healthcare services and the relatively affordable costs attract international patients seeking medical treatment.

Education Update 02/24/2026

The education system in Malaysia consists of kindergarten education, followed by six years of compulsory primary education and five years of optional secondary education. Kindergarten education is non-compulsory, but it serves as a preparatory stage for children before entering primary school.

Primary schools in Malaysia are divided into two categories: national primary schools and vernacular schools. National primary schools use the Malay language as the medium of instruction, while vernacular schools offer education in Chinese or Tamil languages. Parents can choose to enroll their children in either type of school based on their language preferences and cultural background.

Secondary education in Malaysia lasts for five years and is divided into lower secondary and upper secondary levels. At the end of the upper secondary level, students take the Malaysian Certificate of Education examination, commonly known as Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM). The SPM examination serves as a benchmark for students’ academic achievement and is an important qualification for further education or employment.

In 1999, the matriculation program was introduced, providing an alternative pathway for students to enter local universities. This 12-month program is designed to prepare students for higher education and offers admission to local universities upon completion. However, it’s important to note that in the matriculation system, only 10% of places are open to non-bumiputera (non-indigenous) students, which has been a topic of discussion and debate in Malaysia.

The education system in Malaysia continues to evolve, with ongoing efforts to improve the quality and accessibility of education. The government places emphasis on promoting a well-rounded education that encompasses academic, vocational, and technical skills to meet the needs of a diverse society.

Culture Update 02/24/2026

Malaysia is known for its diverse and vibrant cultural landscape, influenced by various ethnic groups and historical factors. The indigenous tribes and Malays form the foundation of the country’s original culture, and their customs, traditions, and languages contribute to the multicultural fabric of Malaysia. Over time, significant cultural influences from Chinese and Indian communities have also shaped Malaysian society, dating back to the era of foreign trade.

In addition to the indigenous, Malay, Chinese, and Indian cultures, Malaysia has also been influenced by Persian, Arabic, and British cultures. The rich blend of these cultural elements has resulted in a unique Malaysian identity that celebrates diversity.

To manage cultural diversity and maintain social harmony, the government implemented the “National Cultural Policy” in 1971. The policy aimed to define Malaysian culture, emphasizing the incorporation of suitable elements from various cultures while maintaining the primacy of indigenous culture and the importance of Islam. The promotion of the Malay language was also a significant aspect of the policy.

However, the government’s intervention in culture and the emphasis on Malay culture and language have led to discontent among non-Malay communities. Some non-Malays feel that their cultural freedom has been restricted, leading to tensions and cultural disputes, particularly with neighboring Indonesia.

Chinese and Indian associations have expressed their concerns to the government through memorandums, criticizing what they perceive as an undemocratic cultural policy. These disputes reflect the challenges of balancing cultural diversity and national identity in a multi-ethnic society like Malaysia.

It’s important to note that culture is a dynamic and evolving aspect of society, and Malaysia continues to navigate the complexities of cultural diversity while striving for social cohesion and inclusivity.

Fine arts

Traditional Malaysian art encompasses a variety of crafts and artistic practices, with a focus on carving, weaving, and silversmithing. These art forms reflect the rich cultural heritage of Malaysia. Carvings can be seen in various objects, ranging from intricate ornamental kris (traditional Malay daggers) to beetle nut sets. Weaving is a traditional skill, producing beautiful handwoven baskets and fabrics such as batik and songket. The Malay courts are known for their exquisite silverwork.

Indigenous communities in East Malaysia are renowned for their wooden masks, which hold significant cultural and spiritual significance within their traditions.

Each ethnic group in Malaysia has its own distinct performing arts, showcasing a diverse range of artistic expressions. Traditional Malay music and performing arts have origins in the Kelantan-Pattani region and have been influenced by Indian, Chinese, Thai, and Indonesian cultures. Percussion instruments, particularly the gendang (drum), play a central role in traditional Malay music. Various types of traditional drums are used, often crafted from natural materials. Traditional music is employed for storytelling, marking important life-cycle events, and celebrating occasions like harvest festivals. In East Malaysia, gong-based ensembles like agung and kulintang are commonly used in ceremonies, similar to neighboring regions such as Mindanao in the Philippines, Kalimantan in Indonesia, and Brunei.

Malaysia has a rich oral tradition that predates written records and continues to thrive today. Each Malay Sultanate developed its own literary tradition, drawing on oral stories and Islamic narratives. Early Malay literature was written using the Arabic script, with the Terengganu stone dating back to 1303 being one of the earliest known examples. As the Chinese and Indian communities grew, their literary traditions also became prominent in Malaysia. In the 19th century, locally produced works in Chinese and Indian languages emerged. English has also become a common language in Malaysian literature. In 1971, the government classified literature based on the language used, distinguishing between national literature (in Malay), regional literature (in other indigenous languages), and sectional literature (in other languages).

Malay poetry holds a significant place in the literary scene, employing various forms and structures. The Hikayat form of storytelling is popular, and the pantun (a form of poetry) has spread beyond Malay to other languages in the region.

Cuisine

Malaysia’s cuisine is a vibrant reflection of its diverse population, drawing influences from various cultures within the country and neighboring regions. The culinary traditions of Malay, Chinese, Indian, Thai, Javanese, and Sumatran cultures have all contributed to the rich tapestry of Malaysian cuisine. The country’s historical position along the ancient spice route has further enriched its culinary landscape.

Malaysian cuisine shares similarities with the cuisines of Singapore and Brunei, and also exhibits some resemblances to Filipino cuisine. However, each state within Malaysia has its own unique dishes, adding further diversity to the culinary scene. It’s worth noting that Malaysian cuisine may differ from the original dishes of specific cultures due to adaptations and regional variations.

One fascinating aspect of Malaysian food is the assimilation of dishes from different cultures. For instance, it is not uncommon to find Chinese restaurants in Malaysia serving Malay dishes, showcasing the blending of culinary influences. Additionally, cooking styles and ingredients are often borrowed and incorporated across cultures. A classic example is the use of sambal belacan (shrimp paste), which is widely used by Chinese restaurants to prepare stir-fried water spinach (kangkung belacan). This fusion and cross-cultural exchange have resulted in Malaysian dishes having their own distinct identity, even though they may trace their origins back to specific cultures.

Rice plays a central role in Malaysian cuisine and is considered a staple food. It holds great cultural significance and is consumed in various forms. Chili is another commonly used ingredient, although not all Malaysian dishes are spicy. The use of chili adds flavor and depth to many dishes, contributing to the complexity of flavors in Malaysian cuisine.

Overall, Malaysian cuisine is a delightful amalgamation of flavors, techniques, and ingredients from diverse cultural influences, making it a true reflection of the country’s multi-ethnic society.

Media

In Malaysia, the ownership of main newspapers is largely dominated by the government and political parties within the ruling coalition. However, major opposition parties also have their own newspapers, which are openly sold alongside regular publications. There is a noticeable divide in media coverage between the two halves of the country. The media in Peninsular Malaysia tends to give low priority to news from the eastern states, often treating them as colonies rather than equal regions.

To address the limited coverage and representation of the eastern states, Sarawak, in East Malaysia, launched TV Sarawak as an internet streaming platform in 2014 and as a television station on 10 October 2020. This initiative aimed to overcome the media bias and strengthen the representation of East Malaysia.

The media has been criticized for exacerbating tensions between Indonesia and Malaysia, as well as perpetuating negative stereotypes of Indonesians among Malaysians. Malaysia has newspapers published in Malay, English, Chinese, and Tamil. However, news specifically for the Kadazandusun and Bajau communities is only available through TV broadcasts such as Berita RTM. Written Kadazan news was previously included in publications like The Borneo Post, the Borneo Mail, the Daily Express, and the New Sabah Times, but their publication has ceased with the closure of the newspapers or specific sections.

Freedom of the press in Malaysia is limited, and there are numerous restrictions on publishing rights and information dissemination. The government has previously taken actions to suppress opposition papers ahead of elections. In 2007, a government agency issued a directive to private television and radio stations, instructing them not to broadcast speeches made by opposition leaders. This move was condemned by politicians from the opposition Democratic Action Party. Sabah, where most tabloids are independent of government control, is considered to have the freest press in Malaysia. Laws such as the Printing Presses and Publications Act have also been criticized for curtailing freedom of expression in the country.

Holidays and festivals

Malaysia is known for its rich diversity of holidays and festivities celebrated throughout the year. These include both federally gazetted public holidays and those observed by individual states. Some festivals are specific to certain ethnic or religious groups, and the main holiday of each major group is declared a public holiday.

See more:Best time for Malaysia travel 2024

One of the most significant national holidays is Hari Merdeka (Independence Day) on 31 August, which commemorates the independence of the Federation of Malaya in 1957. Malaysia Day on 16 September celebrates the formation of Malaysia in 1963. Other notable national holidays include Labour Day on 1 May and the King’s birthday, which is typically observed in the first week of June.

As Islam is the state religion, Muslim holidays hold prominence in Malaysia. Hari Raya Puasa (also known as Hari Raya Aidilfitri), Hari Raya Haji (also known as Hari Raya Aidiladha), and Maulidur Rasul (the birthday of the Prophet) are among the important Muslim holidays observed in the country.

Malaysian Chinese celebrate festivals such as Chinese New Year and other traditional Chinese beliefs. Wesak Day is celebrated by Buddhists, and Hindus in Malaysia observe Deepavali, the festival of lights. Thaipusam is a religious rite that brings together pilgrims from all over the country at the Batu Caves. Malaysia’s Christian community celebrates major Christian holidays like Christmas and Easter.

Additionally, various indigenous communities in Malaysia have their own unique festivals. The Dayak community in Sarawak celebrates Gawai, a harvest festival, while the Kadazandusun community celebrates Kaamatan.

Despite many festivals being associated with specific ethnic or religious groups, the spirit of celebration is universal in Malaysia. A practice known as “open house” is observed, where Malaysians of different backgrounds participate in the festivities of others. It is common for people to visit the homes of those celebrating a particular festival, fostering a sense of unity and cultural exchange.

Sports

Malaysia is home to a variety of popular sports enjoyed by its people. The most popular sport in the country is association football (soccer). Football matches attract a large following, and Malaysia has a strong football culture. Badminton is another highly popular sport, with Malaysia being one of the leading countries in the sport. Malaysia has a successful badminton team and has won the prestigious Thomas Cup multiple times.

Other popular sports in Malaysia include field hockey, bowls, tennis, squash, martial arts, horse riding, sailing, and skateboarding. The Malaysian national field hockey team has achieved international recognition and has participated in major tournaments such as the Hockey World Cup. The country also has its own Formula One racetrack, the Sepang International Circuit, which has hosted the Malaysian Grand Prix.

Traditional sports are also valued in Malaysia, with Silat Melayu being the most common style of martial arts practiced by ethnic Malays.

Malaysia actively participates in international sporting events. The Olympic Council of Malaysia, formerly known as the Federation of Malaya Olympic Council, has been sending athletes to the Olympic Games since 1956. Malaysia has also participated in the Paralympic Games. Additionally, Malaysia has been a regular participant in the Commonwealth Games since 1950, and the games were even hosted in Kuala Lumpur in 1998.

Sports play an important role in Malaysian society, fostering a sense of national pride and unity among its people.